Jaap Maat

University of Amsterdam

1. The Popham notebook

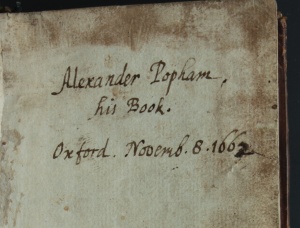

In the summer of 2008, a leather-bound booklet attracted the attention of a member of staff of Warner Leisure Hotels in Littlecote House, near Hungerford, Wiltshire, UK. It looked old, and in fact it was. It turned out to be a seventeenth-century notebook, filled for the most part with hand-written text. On the title page it said: “Alexander Popham, his book. Oxford, Novemb. 8. 1662”.

In the summer of 2008, a leather-bound booklet attracted the attention of a member of staff of Warner Leisure Hotels in Littlecote House, near Hungerford, Wiltshire, UK. It looked old, and in fact it was. It turned out to be a seventeenth-century notebook, filled for the most part with hand-written text. On the title page it said: “Alexander Popham, his book. Oxford, Novemb. 8. 1662”.

It soon became clear that this notebook was a fascinating find, as it promised to shed light on a famous case in the history of teaching language to the deaf. Littlecote House used to be the home of the Pophams, a wealthy family whose members were admirals and judges playing an important role in early modern political history. Alexander Popham was born deaf, and remained mute until he was about ten years old.

He then was taught, at least in part successfully, how to speak, read and write, by two teachers: first by William Holder (1616-1698), and subsequently by John Wallis (1616-1703). The recently discovered notebook is written in the hand of Wallis, Popham’s second teacher, and it is obvious from its contents that it was composed by Wallis specifically for the purpose of instructing Popham.

He then was taught, at least in part successfully, how to speak, read and write, by two teachers: first by William Holder (1616-1698), and subsequently by John Wallis (1616-1703). The recently discovered notebook is written in the hand of Wallis, Popham’s second teacher, and it is obvious from its contents that it was composed by Wallis specifically for the purpose of instructing Popham.

The case of Alexander Popham has primarily become famous for two reasons. First, although he was not the first person born deaf in Western history to succeed in acquiring command of a language of the hearing, to do so was certainly a rare and remarkable achievement. Until the sixteenth century, it was generally considered impossible to cure deafness or to find a remedy for muteness other than to have recourse to signing, which was typically seen as at best a very deficient substitute for spoken language. In 16th-century Spain, the first systematic attempts were undertaken to teach written and spoken language, in this order, to deaf-mutes (Plann, 1997). These attempts reportedly succeeded, and although Holder and Wallis must have been aware of this, they considered themselves pioneers. Secondly, both teachers of Popham afterwards claimed the credit for this success, which led to a bitter dispute between them. The dispute attracted more attention from historians than the average petty quarrel between rival scholars as it was fought out in print, and took place within the early Royal Society, involving as it did two of its prominent members, who both appealed to other fellows in support of their claims.

In what follows, I summarize the debate between Holder and Wallis before briefly returning to the Popham notebook.

2. Teaching of Alexander Popham (1659-1662)

In 1659, when Alexander Popham was 10 years old, his parents entrusted him to the care of William Holder, who undertook to teach him to speak. It is unknown why Alexander’s parents turned to Holder, a clergyman who was to become a leading phonetician and musicologist in later years, but had not published on those subjects at the time.

In 1659, when Alexander Popham was 10 years old, his parents entrusted him to the care of William Holder, who undertook to teach him to speak. It is unknown why Alexander’s parents turned to Holder, a clergyman who was to become a leading phonetician and musicologist in later years, but had not published on those subjects at the time.

Alexander stayed with Holder for about a year, and as Holder later claimed, his teaching met with spectacular success. Popham was able to pronounce words “plainly and distinctly, and with a good and graceful tone” (Holder 1678, p. 5). According to Holder, this was seen as an extraordinary achievement, which attracted many visitors to his house at Bletchington near Oxford, who came there to see and hear the deaf boy speak. Among these were not only men like Ward, Wilkins, and Bathurst, who (just like Holder and Wallis) were to become founders or fellows of the Royal Society, but also, or so Holder claimed, John Wallis – a claim that was categorically denied by the latter. Holder further asserted that he took his pupil to London, where the boy’s relatives, and “many persons of all degrees satisfied themselves in hearing Mr. Popham speak” (Holder 1678, p. 5). After about a year, Holder’s teaching was broken off as he moved to another parish.

Two years after that, in September 1662, Alexander was brought to John Wallis, for the same purpose: to teach language to him.

Two years after that, in September 1662, Alexander was brought to John Wallis, for the same purpose: to teach language to him.

Wallis had acquired a reputation as a teacher of a deaf person in that same year. In December 1661, he started teaching Daniel Whaley, then some 25 years old, who had lost his hearing at the age of five, and subsequently lost his ability to speak. Wallis managed to make Whaley pronounce several words, a result which he showed to a meeting of the newly established Royal Society in May, 1662. He also showed Whaley to the king and his court in London shortly afterwards. It is understandable, then, that Popham’s mother asked Wallis to take care of his further education. Wallis, according to his own account, had never met young Popham before he took him on as a pupil, thus contradicting Holder’s version of the events. Furthermore, when Popham entered his tuition, he was unable to utter a single word, and lacked every ability in the use of English. The latter claim was not contested by Holder, but could be easily explained by him: as Popham’s education had been incomplete, and he had had no further practice, he lost everything that Holder had taught him in the two years between his own teaching ended and that by Wallis began.

3. The dispute (1678)

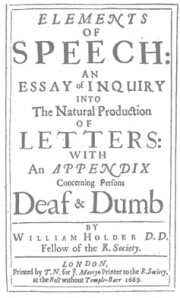

The actual dispute between Holder and Wallis did not take place until 1678, sixteen years after the events. However, to understand what fuelled the quarrel, it is necessary to mention a few things that occurred in the meantime. In 1669, Holder published his ‘Elements of Speech’, which contained a sophisticated analysis of speech sounds according to articulatory principles. It also contained ‘an appendix concerning persons deaf and dumb’, in which Holder explained how a deaf person could be instructed to produce speech sounds.

The actual dispute between Holder and Wallis did not take place until 1678, sixteen years after the events. However, to understand what fuelled the quarrel, it is necessary to mention a few things that occurred in the meantime. In 1669, Holder published his ‘Elements of Speech’, which contained a sophisticated analysis of speech sounds according to articulatory principles. It also contained ‘an appendix concerning persons deaf and dumb’, in which Holder explained how a deaf person could be instructed to produce speech sounds.

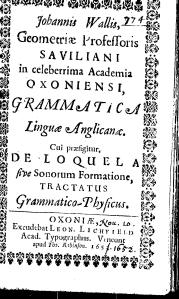

It is not completely certain, but extremely likely that it was in reaction to Holder’s publication that Wallis felt it necessary to point publicly at his own achievements both in articulatory phonetics and in teaching language to deaf persons. In 1670, he published, in the Philosophical Transactions, the Royal Society’s journal, a letter written by himself in 1662, when he was teaching Whaley, in which he explained to Robert Boyle what progress he had made in this. He added a short but unsigned postscript, mentioning that ‘Dr. Wallis’ had later also successfully taught ‘a young Gentleman of a very good family’, who was born deaf, clearly intending Popham (Wallis 1670, p. 1098). The postscript also drew attention to the fact that Wallis had given a thorough analysis of speech sounds in his ‘De Loquela’, published in 1653.

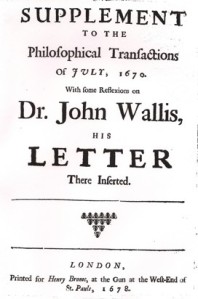

The publication in 1670 of Wallis’s letter to Boyle, and especially its postscript, infuriated Holder. In his view, Wallis was trying to appropriate the credit for teaching Popham as exclusively his own, whereas in fact it belonged chiefly to himself, as his first teacher. What Wallis could boast was to have revived, not to have developed a skill in Popham, just as happened with his other pupil Whaley, who must have had speech as a young child. Besides, the skills of Whaley that were displayed to the Royal Society meeting were rather poor: he was able to pronounce a few words “with a harsh ill tone” (Holder 1678, p. 6). Holder gritted his teeth in silence for years, until he saw another publication (Plot’s Oxfordshire, Plot 1677) in which Wallis’s achievements (which did not concern Popham) were extolled in the third person, although, Holder was convinced, Wallis had penned the entire eulogy of Dr. Wallis himself, just as in the wretched postscript of 1670. In 1678, Holder decided to expose Wallis’s devious ways in a pamphlet entitled ‘A Supplement to the Philosophical Transactions of July, 1670, with some reflexions on Dr. John Wallis, his Letter there inserted’, in which he explained what ‘subtle contrivances’ Wallis had used to reap the fruit of another person’s labour, driven by an excessive greed of fame.

The publication in 1670 of Wallis’s letter to Boyle, and especially its postscript, infuriated Holder. In his view, Wallis was trying to appropriate the credit for teaching Popham as exclusively his own, whereas in fact it belonged chiefly to himself, as his first teacher. What Wallis could boast was to have revived, not to have developed a skill in Popham, just as happened with his other pupil Whaley, who must have had speech as a young child. Besides, the skills of Whaley that were displayed to the Royal Society meeting were rather poor: he was able to pronounce a few words “with a harsh ill tone” (Holder 1678, p. 6). Holder gritted his teeth in silence for years, until he saw another publication (Plot’s Oxfordshire, Plot 1677) in which Wallis’s achievements (which did not concern Popham) were extolled in the third person, although, Holder was convinced, Wallis had penned the entire eulogy of Dr. Wallis himself, just as in the wretched postscript of 1670. In 1678, Holder decided to expose Wallis’s devious ways in a pamphlet entitled ‘A Supplement to the Philosophical Transactions of July, 1670, with some reflexions on Dr. John Wallis, his Letter there inserted’, in which he explained what ‘subtle contrivances’ Wallis had used to reap the fruit of another person’s labour, driven by an excessive greed of fame.

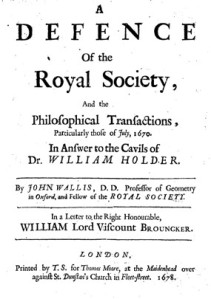

Wallis was quick to respond. In the same year, 1678, he published ‘A defence of the Royal Society, and the philosophical transactions, particulary those of July, 1670, in answer to the Cavils of Dr. William Holder’, a lengthy piece in which Holder’s accusations were answered in great detail. The thrust of the argument was that Holder had got a central fact wrong: Wallis had never witnessed any results obtained by Holder in teaching Popham. He did know that Holder had attempted to teach language to Popham, but when his mother brought the boy to him, which was when Wallis first met him, he could not utter or understand a single word of English.

Wallis was quick to respond. In the same year, 1678, he published ‘A defence of the Royal Society, and the philosophical transactions, particulary those of July, 1670, in answer to the Cavils of Dr. William Holder’, a lengthy piece in which Holder’s accusations were answered in great detail. The thrust of the argument was that Holder had got a central fact wrong: Wallis had never witnessed any results obtained by Holder in teaching Popham. He did know that Holder had attempted to teach language to Popham, but when his mother brought the boy to him, which was when Wallis first met him, he could not utter or understand a single word of English.

Wallis concluded that Holder’s teaching must have been completely unsuccessful, for it was unlikely that Popham could have forgotten everything in the space of two years.  It would therefore have been embarrassing for Holder if Wallis had mentioned the former’s previous teaching in his 1670 postscript. Rather than being disingenuous, he had acted out of politeness in passing over it. In sum, Holder had tried in vain what Wallis accomplished afterwards, and was now complaining that he was deprived of the credit for something he never achieved. Wallis did not forget to emphasize that his own success in teaching Popham to speak was based on his theory of articulatory phonetics, published in 1653, that is, many years before Holder published anything on that subject.

It would therefore have been embarrassing for Holder if Wallis had mentioned the former’s previous teaching in his 1670 postscript. Rather than being disingenuous, he had acted out of politeness in passing over it. In sum, Holder had tried in vain what Wallis accomplished afterwards, and was now complaining that he was deprived of the credit for something he never achieved. Wallis did not forget to emphasize that his own success in teaching Popham to speak was based on his theory of articulatory phonetics, published in 1653, that is, many years before Holder published anything on that subject.

4. Shared assumptions, different approaches

The controversy between Holder and Wallis was clearly related to a number of diverse issues, one of which was the question of who was the better phonetician. But perhaps more interesting than their rivalry in this respect is the fact that they agreed on the principle that teaching speech to a person born deaf should be based on a correct theory about the production of speech sounds. They both presented their real or alleged success in teaching Popham as a direct consequence of such a theory. As far as the more futile aspect of the debate is concerned, it is clear that it hinged on contradictory answers to two questions: first, did Holder manage to teach Popham to pronounce words distinctly, and, second, if so, did Wallis know this?

It is noteworthy that Holder’s claim did not go any further than that Popham was able to pronounce words. It is apparent from his own description of his method in the appendix to the Elements of Speech, that his teaching never went beyond that stage. He intended to pay attention to grammar, and to the meaning of words, but he never got round to that (Holder 1669, p. 157). Thus, his approach reflected his preoccupation with phonetics, and it seems likely that whatever he taught Popham, this could not have been of any use to the boy. It is also likely that without continued practice anything Popham did learn was soon lost again. As appears from the Popham notebook, and also from his letters, Wallis realised that it was essential for the deaf pupil to understand language, and that the capacity to utter words without understanding was useless.

5. The notebook and the debate

The Popham notebook does not contain any material that could resolve the dispute between Holder and Wallis. It may by now be clear why it could hardly have contained such material. After all, it was written by Wallis for the purpose of teaching a deaf boy, who, according to both disputants, was unable to say or understand a word of English when Wallis’s tuition began. Of course, this does not mean that the notebook is not an extremely interesting find. Not only has it occasioned us to review a famous but poorly investigated controversy once more, but it gives detailed insight into the actual method used by Wallis in his teaching of Popham. The outlines of this method were sketched by Wallis in a letter to Beverley in 1698, but now the notebook has emerged we are able to fill in many of the details. Semantics and grammar were at least as important as the production of speech sounds in Wallis’s method, and this is reflected in the contents of the notebook.

This post might get too long if I were to go into the contents of the notebook any further. We are preparing an edition of it, which is shortly to appear (Cram and Maat, forthcoming). The edition will also contain the relevant letters and pamphlets, as well as an introduction in which the broader context of teaching language to the deaf is discussed.

References

Cram, David and Jaap Maat. Forthcoming. The Popham Notebook. John Wallis’s Manual for Teaching Language to a Boy Born Deaf. Oxford University Press.

Holder, William. 1669. Elements of Speech: An Essay of Inquiry into the Natural Production of Letters’ with an Appendix concerning persons Deaf & Dumb. London.

Holder, William. 1678. A Supplement to the Philosophical Transactions of July 1670, with some reflexions on Dr John Wallis, his letter there inserted. London.

Plann, Susan. 1997. A Silent Minority, Deaf Education in Spain, 1550-1835. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.

Plot, Robert. 1677. The natural history of Oxford-shire, being an essay toward the natural history of England. Oxford.

Wallis, John. 1653. Grammatica Linguae Anglicanae. Cui praefigitur, De Loquela, sive Sonorum Formatione, Tractatus Grammatico-physicus. Oxford.

Wallis, John. [letter dated 1662] 1670. ‘A letter of Dr. John Wallis to Robert Boyle Esq, concerning the said Doctor’s Essay of Teaching a person Dumb and Deaf to speak, and to Understand a language’. Philosophical Transactions, 1670, vol. 5, pp. 1087-97.

Wallis, John. 1678. A Defence of the Royal Society, and the Philosophical Transactions, particularly those of July, 1670: In answer to the cavils of Dr. William Holder. London.

Wallis, John. 1698. ‘A letter of Dr. John Wallis to Mr. Thomas Beverley.’ Philosophical Transactions, October 1698, vol. 20, pp. 353-360.

How to cite this post

Maat, Jaap. ‘Teaching language to a boy born deaf in the seventeenth century: the Holder-Wallis debate’. History and Philosophy of the Language Sciences. https://hiphilangsci.net/2013/11/06/teaching-language-to-a-boy-born-deaf-in-the-seventeenth-century-the-holder-wallis-debate

I should have mentioned that in 2012, Peter Jackson of the British Deaf History Society published a book on the Popham notebook, containing biographical details of Alexander Popham and a number of pictures of the notebook. See http://www.bdhs.org.uk/shop/alexander-pophams-notebook/

I am sure you must have seen this:

Conrad, R. & Weiskrantz, B. 1984: Deafness in the 17th Century: Into empiricism in Sign Language Studies 45 Winter

The Wallis & Holder debate is described here too.

[…] became embroiled in a dispute about who was most successful in teaching Alexander Popham, a boy born deaf. Although […]